“And he lifted his eyes and saw Benjamin, his brother, the son of his mother” (Genesis, 43:29), Parashat Miketz.

The weekly portion of Miketz continues the story of Joseph and does not end, but leaves us with the great drama about what he will do with Benjamin and the “goblet” that was found in his sack. From the dealings with Joseph and his brothers, we can now turn our attention to Joseph and his brother, the son of his mother, and the youngest son of his father.

We are not told much about Benjamin, Jacob’s youngest son, amongst the many chapters that we read about his brothers and other personalities. He is described as the son of his mother, who did not live until an old age and therefore, his father places him on his right, where he can protect him, supervise him and not let him “bring his sorrow down to the grave.” We do not see that Benjamin does anything independently, as he becomes the center of the drama, even for a few moments. Benjamin remains one who is connected to more prominent personalities: his mother, brother, father and, at the end of the chapter, to his brothers who protect him.

Since his birth, from the one who remains the only son of Rachel for many years to his future after receiving the blessing of Jacob – Benjamin does not receive much attention. We will now stop and look at him for a moment. The power of this moment will be in the minimum specific weight – these are the women, the children, the elderly or the silent, weak or transparent in various descriptions … also here, we must hesitate and look at the personality of Benjamin, or more correctly: at what happens to him, and about him.

The biography of Joseph is not like the biography of Benjamin, despite the same differences, the brothers who are a minority among the twelve sons of Jacob. Benjamin, who never had any years with his mother Rachel, lived as if she was present-absent and from a certain point in his life, even his elder brother is absent. Benjamin is not counted separately from Jacob’s other sons. In addition to the fact that he is Rachel’s only son, unlike the sons who have other mothers, he does not undermine the unique personality of Joseph, but he also does not receive any compassion because of his loneliness, the family “poverty” that he experiences from the moment of his birth, and which is underscored with his brother’s disappearance.

When the brothers arrive in Egypt with Benjamin, Joseph has to recover from the excitement in a separate room, but he also creates a situation where he can ask them the big question: “What is this that you have done?” (Genesis, 44:15), apparently in regard to the attempted theft that he was accused of. This question can also refer to the other act that they performed against him. The hiding brother, Joseph, makes the brothers once again deal with an outsider brother and make a decision about him. Joseph might have done this to reconstruct something from his past and expects them to predict what would be done with Benjamin regarding the theft.

Benjamin, the youngest son, and orphan from day one, is put into a more extreme situation and does not receive any empathy, just like during his lifetime until now. Nobody talks to him, nobody approaches him, but they protect him because of their commitment to Jacob. This attitude might arouse a significant experience – Benjamin is not important in the events that might have caused him to be enslaved to the Egyptian ruler, but rather the brothers’ fear of their father is what saves him. Benjamin does not say a thing, he does not defend himself against the accusation of stealing, and we do not hear his opinion – on the one hand, he is defended, but on the other, events are happening over him, above his head and do not let him express himself or take a stand.

In the summer of 5762 (2002) the Neue Synagoge in Berlin displayed an exhibition of Bible paintings by artists Ury Lesser (1861-1931). I was visiting Berlin at the time and when stopped to look at the paintings of Benjamin, realized that he is a tragic story that was not told, he was overcast by Joseph, orphaned at birth, lost a brother for many years, was lonely because he was much younger than the brothers who remained with his father.

One of the paintings (to the best of my knowledge) showed Jacob blessing Benjamin. The brother look big and looming and only Benjamin is like a young “Mowgli,” standing aside, with small shoulders and big eyes, receiving the blessing and probably not perceiving the impending death in his family. The childish Benjamin (as Lesser sees him, without calculating ages like the Torah commentators) is about to also experience the death of his brother Joseph and remain alone, without anyone else of his core family. It is natural that the younger family members bury their elder, but Benjamin buried his mother when he was born, without holding onto the body whose smells he knew. Benjamin was thrown into independence, but nobody deals with him.

I saw the painting, but did not take a photo of it. Still, I remember its height, colors and strength in placing Jacob and his sons, with Benjamin separate and different.

I found some of the experience of this painting in the words of Martin Buber (in 1903), on the landscape paintings by Ury Lesser:

“To such an extent the landscapes of my light lack any content, so surreal, that one can almost not explain them, but see and sense them only”.

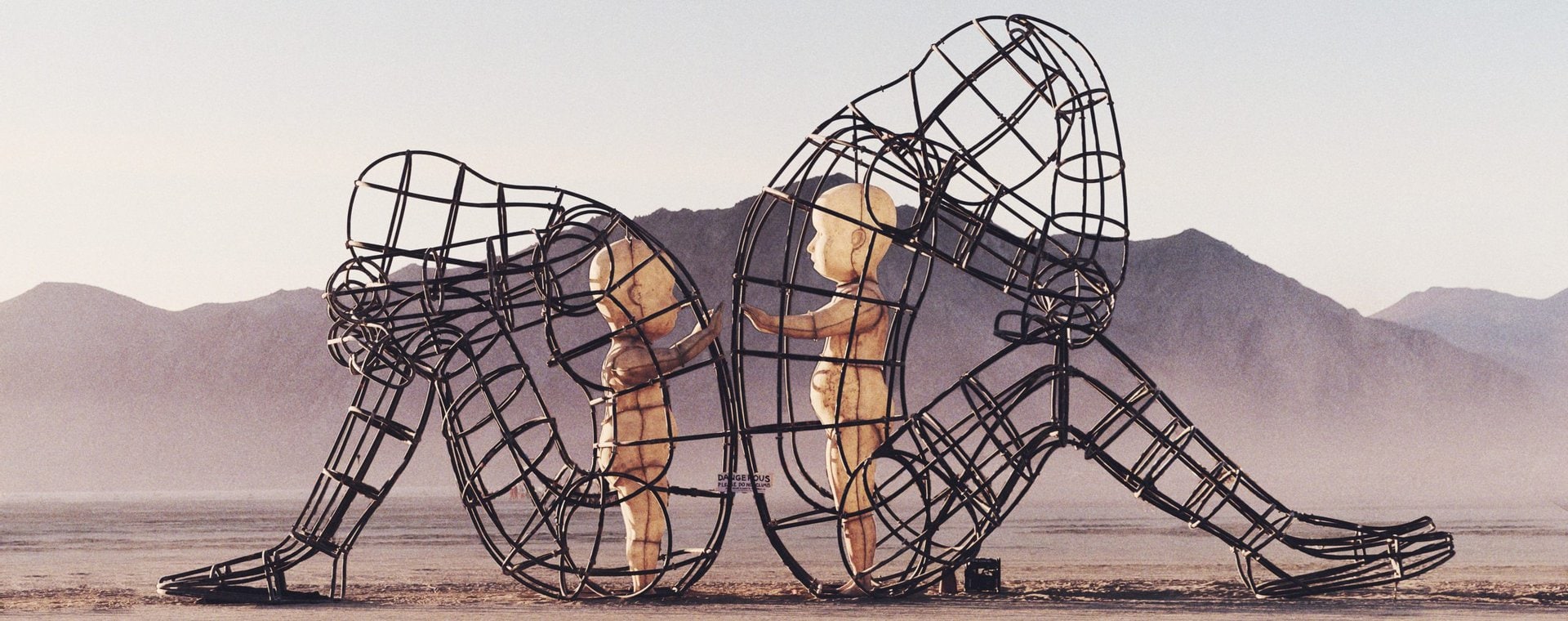

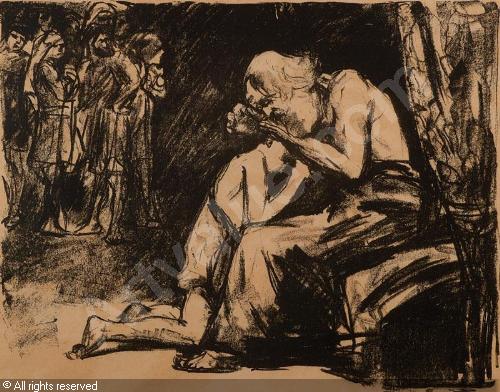

In order to display some real visualization we will look at another painting by Ury Lesser. This painting is available online: Jacob blessing Benjamin, which appears in two versions:

Colorful, painted in 1884:

And black and white, painted in 1920:

The first version shows a private scene where Benjamin is standing alone with his father, and in the second one we can see the older brothers in the background, so the scene is not totally private.

Ury painted Benjamin next to his father in a way that echoes the warmth that he missed, reflecting the childish Benjamin in comparison to his old father. (Buber states that the biblical material entitled “Jacob blesses his son Benjamin” was destroyed sometime after it was created – I do not know which work of art he was referring to, but I assume it was to the earlier, colorful painting. I saw this one at the exhibition, but have not found it online).

In our Parasha, Jacob, Joseph, the brothers – are all alive, alive on a journey where the secret has not yet been told and the unification has not been completed. The quiet death has not yet occurred. If within the collection of stories about Joseph, we also look at the weaker members, the ones who rely on protection without choice, but do not sound their voice – we will engage in a significant reading when identifying the silenced-silent voice, a voice that sometimes wishes to accept this situation and sometimes cries out to be heard in silence.

Then we will look, but we will not force the voice to be heard, but the eye that did not look before, the heart that did not stay with Benjamin and Benjamin as a symbol. Such a reading, even if it refers to male personalities (as the biblical casting in our Parasha), proves that the moral voice that searches for the one who was made little, by no choice of his own, was internalized, in order to evoke a new spirit and recognition that brings out from the hidden and silent.

Published in the weekly brochure of Kolech, Forum of Religious Women, on Parashat Miketz, 5777.

Read Hebrew version: מיוסף ואחיו ליוסף ואחיו